5 Conditions for Writing and Meditation, Part Two

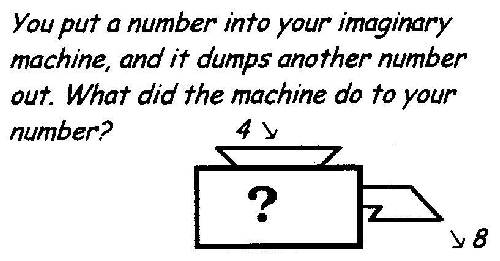

4. Enthusiasm. The first three conditions (that I wrote about last week) are tangible. This one is a bit more abstract. I like that Ricard includes 2 possible sources for enthusiasm: thinking about the benefits and then getting a taste of them. For me, with writing, the latter happened first. I wrote and I tasted the benefits and that motivated me to want to continue. I only learned about possible benefits in a theoretical sense much later. But with meditation, for me, it’s been the other way around. I’ve been hearing about the benefits for years—and it was hearing about this—from many different people—that eventually gave me some enthusiasm to want to try it—and then to begin to taste the benefits. To me one of the appealing benefits of meditation is to develop a more stable mind, to become less blown by the winds of this day and that. As a high school teacher now, I find the wind is often blowing this way and that—both inside the classroom and outside—and I’ve gradually come to realize I need a more stable mind in order to handle the wind better. Yes, I think now that it’s teaching that has been one of the things propelling me towards meditation—to realize that when I have a bit more of a stable mind so does the classroom often become more stable. So I’ve been able to taste the benefits a little and this has motivated me further. 5. Practice & Perseverance. This is something I’ve thought a lot about when it comes to writing. It’s become integral to the way that I think about writing—and is beginning to become part of the way that I think about meditation. Ricard uses an analogy to keeping a plant alive and how important it is to water it regularly. “If you just pour a bucket of water on it once a month, it will most likely die between waterings.” He also talks about not waiting to be motivated by mood, or becoming too dependent on short-term results: “Whether your meditation session is enjoyable or irritating, easy or hard, the important thing is to persevere. . . . Moreover, it is when you don’t feel like meditating that it might have the most beneficial effects, because at those times meditation is working directly against some obstacle that stands in the way of your spiritual progress.” I find this last piece of advice especially useful—and a possible source of enthusiasm when I don’t feel like writing or meditating on a particular day. Ah, it might be even more beneficial because it’s working more directly against this resistance. At the end of the chapter, he reminds us again about thinking long-term rather than short-term: In the case of meditation, your goal is to transform yourself over the course of months and years. The progress you make is usually hardly noticeable from day to day, like the hands of a clock, which you barely see moving. You must be diligent but not impatient. I like to consider that something transformative might be happening slowly and surely even though we often might not be able to see any immediate results. ___________________________________________________________________________ The book, Why Meditate?, can be found here. You can learn more about Matthieu Ricard and his work at matthieuricard.org and...

read more