Odysseus in America: A Book for Healing and Writing

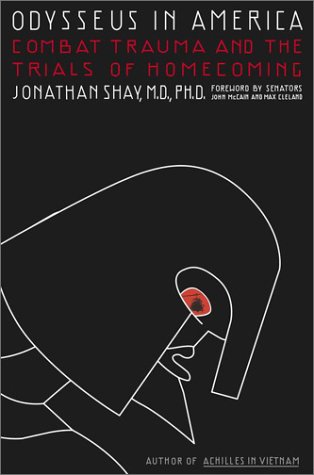

Let me begin with a story about Bear. Bear served one tour in Vietnam as a sergeant in the infantry. During that single tour he was ordered to slit the throat of a wounded enemy soldier. He followed orders. He saw close friends die, including one particularly horrific incident when his platoon, after a night ambush, discovered two headless bodies of their own men; a ways out they came upon the two heads set up on stakes. His platoon went berserk after the incident, cutting off the heads of enemy soldiers, collecting ears. They became known as the headhunters. Back home, a full thirty years out from military discharge, Bear is afraid he’s “losing it”. Bear sleeps on the couch, separate from his wife, with a knife under his pillow. He “walks the perimeter” of his land at night, looking for snipers and ambushes. His job at the post office is in jeopardy because of numerous incidents of violence. He attacks people, sometimes without any provocation. More than once, he’s had to leave work in order to keep himself from killing someone. Jonathan Shay, author of Odysseus in America, looks at this violent man and sees a deep and resonant connection with the Greek hero, Odysseus. I teach high school English now. When I was first starting out, two years ago, I found myself looking for ways to take classic works that are taught in high school—works like The Iliad and The Odyssey and Oedipus Rex—and make them relevant for fifteen and sixteen-year-olds. My search yielded more than I’d hoped for. It led me to the work of Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist who works with war veterans in Boston and who has won for this work the prestigious MacArthur award. Shay was forty years old and conducting research in neuroscience at Massachusetts General Hospital when he suffered a stroke that left him temporarily paralyzed on his left side. While recovering, he decided to read classic works that he’d never gotten around to. He read, among others, The Iliad and The Odyssey. Following his recovery, and with his research stalled, he took a temporary position filling in for a psychiatrist at an outpatient clinic, counseling troubled vets. Connections became apparent—and then multiplied. Shay began to see Achilles in every soldier who’d ever felt betrayed by a commander. He saw Odysseus in every soldier who was having difficulty returning home. Odysseus, Shay reminds us, is the last soldier to make it home from Troy. It takes him ten full years, and for at least some part of the journey he, like Bear, remains in “combat mode.” His first act following combat is a violent one in which he and his men raid the coastal city of Ismarus. Odysseus subsequently travels to Hades, the underworld, where, walking among the dead, he must confront his sense of loss and guilt. He is forced to maneuver between the twin dangers of Scylla and Charbydis. What Shay came to realize is that this ancient story could make a soldier who was struggling with readjustment to civilian life feel less alone—part of something much larger. Shay speaks to this in an interview. “One of the things they appreciate,” he says, “is the sense that they’re part of a long historical context—that they are not personally deficient...

read more