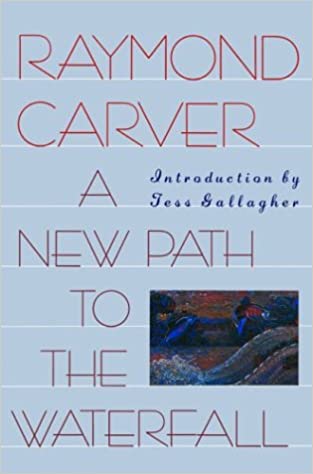

A New Path to the Waterfall by Raymond Carver & Tess Gallagher

This book is the most beautiful example I know of a written mosaic or collage. It began, as near as I can tell, in September of 1987 when Raymond Carver, a gifted writer of both short stories and poems, was diagnosed with lung cancer. The following March the cancer metastasized to his brain, and, then in June, lung tumors recurred. These are the facts that initiated his illness and which Tess Gallagher, his wife, and a gifted poet herself, describes in the introduction to this, Carver’s last book: A New Path to the Waterfall. Tess Gallagher also describes in her introduction the literal making of narrative in the grip of these facts.

First, there are the poems—the elemental pieces of the narrative. Some of these poems Carver had written before the onset of his illness. Many, like “What the Doctor Said,” and “Gravy” and “Late Fragment,” were written and revised during the illness itself. Also during his illness, Tess Gallagher began reading stories by Anton Chekhov and then she began sharing the stories with Carver. During this same time, Carver was reading a book, Unattainable Earth, by Czeslaw Milosz, the polish poet and Nobel laureate. Milosz’s book is a kind of patchwork quilt which incorporates passages from other poets, and this book, according to Gallagher, was key in inspiring Carver to want to find for his own book “a more spacious form”. Then, at some point, something clicked. A new path? First Gallagher, and then Carver, began to see how certain passages in the Chekhov stories could be reconfigured as poems and how these pieces, as well as pieces from other writers, could serve as elements in the narrative that he was trying to make.

Finally, the last step: taking all of these pieces and putting them together to make a narrative. In the introduction to Carver’s book, Gallagher describes spreading poems out on the floor of their living room and literally crawling among them on hands and knees and beginning to arrange them into a pattern: “reading and sensing what should come next, moving by intuition and story and emotion.” It’s a vivid and tactile description of finding a pattern—finding a form. And the result—this book—illustrates (among other things) that a narrative does not have to be linear in order to be beautiful. The gaps become part of its beauty. The breaks. The fault lines. The juxtapositions. The pieces reflecting and refracting, one off of another. And all of that white space around and between.