A Clean, Well-Lighted Place

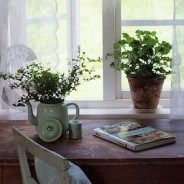

Ernest Hemingway was a genius at creating healing places with words. Here are two. The first is set in Michigan. Hemingway’s family had owned a cottage on a lake in Michigan and he spent summers there as a boy. Consider this place which he recreates in a story called, “Summer People,” one of his Michigan stories. Halfway down the gravel road from Hortons Bay, the town, to the lake, there was a spring. The water came up in a tile sunk beside the road, lipping over the cracked edge of the tile and flowing away through the close growing mint into the swamp. In the dark Nick put his arm down into the spring but could not hold it there because of the cold. He felt the featherings of the sand spouting up from the spring cones at the bottom against his fingers. Nick thought, I wish I could put all of myself in there. I bet that would fix me. It’s the details that bring the place alive. The water lipping over the cracked edge of the tile. The close growing mint. The featherings of sand. A second healing place that Hemingway created is a more famous one—a clean well-lighted place in a story by the same name: In the story an old man sits on the terrace of a café at closing time. It’s late, but the old man, the last customer of the night, is reluctant to leave. A waiter wipes off the old man’s table with a towel and shoos him out. This waiter is eager to get home to his wife, his warm bed. But a second waiter, older than the first, is sympathetic to the old man’s need to linger. First, he tries to explain this to the younger waiter, and then, when the younger waiter loses interest, he tries to explain it to himself, or to whoever will listen—what it is about this particular place that is important: “It is the light of course but it is necessary that the place be clean and pleasant. You do not want music. Certainly you do not want music.” This waiter is very clear about what is necessary for him. This is something writing can do—allow us to become very clear about what is necessary for us. What kind of place? What kind of light? Music?...

read more