Terabithia and Tangalooponda: Healing Places in Books

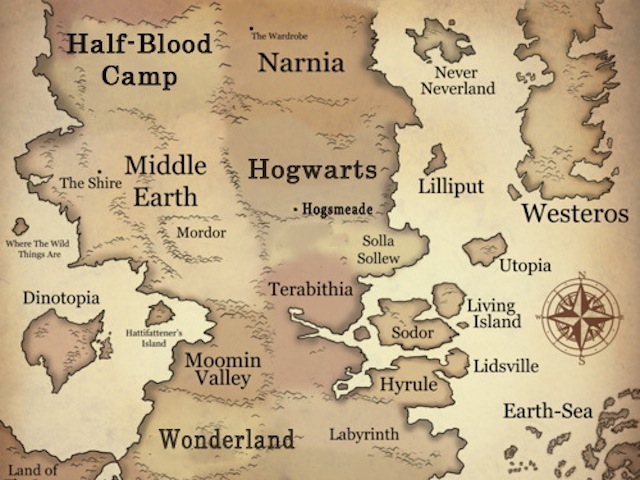

I never had a fort when I was a kid. Maybe that’s why the fort in Bridge to Terabithia holds a particular pull for me. Or maybe it’s the details that Katherine Paterson, the author of the novel, lends it. Jess and Leslie are eleven when they find the perfect place to build their fort—a clearing among dogwood at the edge of the woods. They build the fort out of scrap board. They lay in provisions—clean water in old Pepsi bottles, a coffee can filled with crackers and dried fruit. Then at some point the fort and the land around it become a kingdom—and they give it a name—Terabithia. Such a lovely name.

There’s a passage in the novel where Katherine Paterson describes what it feels like for Jess, the boy, to cross over into Terabithia:

Just walking down the hill toward the woods made something warm and liquid steal through his body. The closer he came to the dry creek bed and the crab apple tree rope the more he could feel the beating of his heart. He grabbed the end of the rope and swung out toward the other bank with a kind of wild exhilaration and landed gently on his feet, taller and stronger and wiser in that mysterious land.

That’s what interests me—right there—the change possible in the body upon entering certain places.

And there’s another place, in another novel—A Map of the World, by Jane Hamilton. The central character, Alice, is looking for her bathing suit one summer morning when she comes upon a series of maps she had drawn as a child. Her mother died when she was a young girl and the maps carry her back to a place, Tangalooponda, that she conjured in the wake of that loss:

I took out the sheaf of papers and knelt down, spread them on the floor, ran my fingers over the lime-green forests, the meandering dark blue rivers, the pointy lavender mountain ranges. I had designed a whole world when I was a child, in secret. I had made a series of maps, one topographical, another of imports and exports, another highlighting mineral deposits, animal and plant species, another with descriptions of governments, transportation networks, and culture centers. My maps had taken over my life for months at a time; it was where I lived, the world called Tangalooponda, up in my room, my tray of colored pencils at my side, inventing jungle animals, the fish of the sea, diplomats and monarchs. Although there were theoretical people in my world, legions of them, all races and creeds, when I imagined myself in Tangalooponda I was always alone, composed and serene as an angel in the midst of great natural beauty.

When I imagined myself in Tangalooponda I was always alone, composed and serene as an angel in the midst of great natural beauty.

Is it possible then?

Can being among natural beauty effect a change in the mind?

Can drawing a map of a place with natural beauty effect this kind of change?

Can writing about natural beauty do this?

Bridge to Terabithia can be found here.

A Map of the World can be found here.

Image from Favim.