Blog

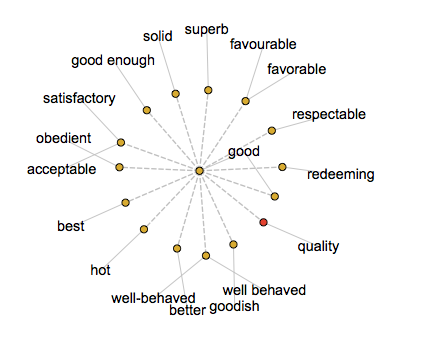

Talking to Grief by Denise Levertov

The title for the chapter, “Making a Place for Grief,” was inspired by and begins with an excerpt from “Talking to Grief” by Denise Levertov: You long for your real place to be readied before winter comes. You need your name, your collar and tag. You need the right to warn off intruders, to consider my house your own and me your person and yourself my own dog. I think there’s a kind of brilliance in this poem, that resonates with so much that I understand about imagery and the way it can help us move through the more difficult passages of our lives. This notion here of imagining grief as a dog. And then taking that next step–speaking to him or her directly. Offering to make her a real place. A home. The chapter begins with her poem and ends then with what seems to me a kind of mirror image: this excerpt from Rumi’s poem, The Guest House, that has become, I suppose, a kind of theme song here: This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival. A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes as an unexpected visitor. Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably. He may be clearing you out for some new delight. This is a kind of goal I’m setting for myself this summer–to become, as much as I’m able, a guest house in this way. To welcome what arrives. I remember the poem sometimes when I’m sweeping my steps and patio in the morning. I remember the way a thought or an emotion–or a wave of emotion–or a person–a snatch of conversation–the line of a poem–or a song–any one of these could come and sweep us clean–prepare us for the next thing. May your summer be a guest house in the best possible way–or perhaps a broom–preparing you for the next thing. ____________________________________________________ Graphic is from Visual...

read moreWhen I Am Asked by Lisel Mueller

I’m not at all sure that June is the right time for grief. But I’m in the process of revising my book, and that’s what I’ve been working on these last couple weeks. It’s interesting. I’ve tended, for a variety of reasons, to look at grief more in November—that’s when I tend to hear and feel most the voices of grief—and to feel a resonance between those voices and the waning light. Now, in a sense, I feel as if I’ve been looking at grief out of season. We’ve also had an especially mild summer so far, with cool, fresh mornings, the windows open, the kind of air that makes me want to be out of doors, walking, and out working in the yard and garden. I’ve been finding a rhythm of writing and then working outside. I’ve cleared and swept the patio and some of the flower beds. I’ve transplanted purple salvia—and dug up an enormous fern for a pot on the patio. I’ve gotten water back into the birdbath and the birds have been coming for drinks. A hummingbird has found the purple salvia. The voices of grief in a new place—a greener, flowering place—with a hummingbird. There’s a poem by Lisel Mueller that speaks to this contrast—the contrast of grief and summer. It begins this way: When I am asked how I began writing poems, I talk about the indifference of nature. It was soon after my mother died, a brilliant June day, everything blooming. I sat on a gray stone bench in a lovingly planted garden, but the day lilies were as deaf as the ears of drunken sleepers and the roses curved inward. Nothing was black or broken and not a leaf fell and the sun blared endless commercials for summer holidays. I can see this—I can see how summer could seem indifferent to difficult feelings and difficult experiences. In her case this itself becomes a catalyst for writing. The poem continues: I sat on a gray stone bench ringed with the ingenue faces of pink and white impatiens and placed my grief in the mouth of language, the only thing that would grieve with me. Placing grief in the mouth of language. This seems important—and wonderful. I can also see how these kind of days—these cool, fresh mornings—could have the potential to offer a kind of balm for grief—as if one were allowing the voice of grief to emerge for a time in a new location—a kind of healing place. With the possibility of finding language there too—in the cool, wet green of summer mornings. ___________________________________ Photo from my patio...

read moreThe Buddha’s Last Instruction by Mary Oliver

During a bittersweet week of graduations, watching a whole flock of students move on, my heart full with their moving, I keep coming back to this poem. Now, only this morning, does it occur to me that the poem describes a kind of graduation speech–a person, in this case Siddhartha Gautama, trying to condense what he learned into a few words. The poem begins this way: “Make of yourself a light,” said the Buddha, before he died. 5 words. Make of yourself a light. The speaker of Mary Oliver’s poem connects this instruction to the rising of the sun itself. I think of this every morning as the east begins to tear off its many clouds of darkness, to send up the first signal—a white fan streaked with pink and violet, even green. I find myself, this morning, the sun already risen, connecting the Buddha’s instructions to tangible light outside my windows, light glowing in the green leaves, and, beyond these trees, I feel the instructions connected to what I see in my mind–a gaggle of students in graduation robes–the light I have seen shine from and among them these last three years that I’ve been with them. The confidence I feel that they will carry this light forward. The sense I have–something a little more than hope–that this extension and expansion of light does not diminish me–their leaving–but somehow extends and expands all of us. A sense I used to have years back when patients graduated from seeing me. A sense I’ve felt at different moments as my own children grow up and away. He might have said anything, Mary Oliver writes. What he said were those 5 words: Make of yourself a light. The speaker of the poem watches and feels the sun blaze over the hills and it’s as if she feels the words themselves in that light I feel myself turning into something of inexplicable value. As if following this instruction could matter? As if following it could make a difference? He could have said anything. he raised his head. He looked into the faces of that frightened crowd. The poem ends on that last line, the pause before the last instructions. And I love that Oliver considers that the crowd was frightened. Transitions always seem to hold that kernel of fear–change is occurring. Nothing’s going to be exactly the way it was before. In this case, a person they loved and looked toward was leaving. What would he tell them? What could he tell them? They must have held their breaths, waiting. And then, after he finally spoke, the words must have echoed inside their heads–and hearts–for the rest of their lives. Oliver, I suspect, intends the words to echo for us as well, at least for a time. She’s constructed her poem, it seems, with that intent. She doesn’t repeat the instructions at the end of the poem. It’s the dropped beat that we inevitably must fill. He looked into the faces of that frightened crowd. A pause. And then he spoke. _______________________________________ See also: A piece on November Angels by Jane Hirshfield...

read moreI must go, I will go: Poetry as Respite and Transformation

In the introduction to his poetry anthology, Through Corridors of Light, which I wrote about a few weeks back, John Andrew Denny writes about how poetry came to offer a respite from the cabin fever imposed by illness. He’d been suffering with ME and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (what is sometimes called CFIDS) when a poem, arriving on a postcard from a friend, catalyzed a shift in his experience. The poem was John Masefield’s “Sea Fever.” His wife had the genius to blow the poem up to poster size and put it up on his bedroom wall. He writes: Until then I had spent most of my days lying on my back, gazing at the ceiling and half-listening to the radio. Now I was just as likely to be lying on my side, focusing my mind on a few lines of the poem. I was mesmerized by the music and the rhythm of its language, and I took comfort in saying its lines over and over like a mantra, which would run through my head at odd times of the day and night. To my delight I found that repeated reading set my imagination alight and briefly transported me out of my prison of boredom and frustration. Saying its lines over and over like a mantra. Every few weeks he changed the poem. . . . when I followed WB Yeats’s imaginary escape from the grey London streets to his ‘Lake Isle of Innisfree’, I felt the exhilaration of freedom from my own narrow London flat, which in reality I could rarely leave. He writes: I found after several months that my feelings of being trapped began to dissolve. Something is happening here. In the first chapter of One Year of Writing and Healing, I write about the importance of discovering and creating and writing about healing places. The way these can become a kind of foundation for healing. But sometimes when one is ill it’s simply asking too much to write. Even reading a book can be too much. But a poem on a poster? Perhaps that could be just the thing. Or perhaps a single line to begin with. Or two lines? I love how, in Denny’s case, the lines of poetry – the music and rhythm of the language – gradually found their way into his mind, transforming thoughts of being trapped, slowly, slowly, into thoughts of finding respite. Something else interesting. Both poems (two of the three he mentions in this section of his introduction) begin in similar and compelling ways. The first, John Masefield’s Sea Fever begins: I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky The Lake Isle of Innisfree has an opening that echoes this: I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree I must go. I will go. Something here I think about what poetry can do–and about what is possible in and with the mind. ________________________________________________ See also: Through Corridors of Light at Amazon Another piece on Through Corridors of Light Sea Fever by John Masefield read aloud on YouTube The Lake Isle of Innisfree by WB Yeats The photo above is of Innisfree, taken by Ben Bulben at Flicker. I like the way you can see the lake water...

read more