One Art by Elizabeth Bishop

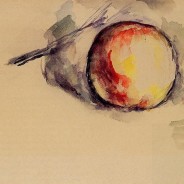

There’s something about this poem, “One Art.” A haunting kind of repetition. It’s a poem about loss and trying to wrap one’s mind around it—trying to master it. It’s about considering loss as an art, which suggests that somehow the loss can be transformed. Can become something of value? Something beautiful? And how exactly? The poem begins with a loss as ordinary as the loss of keys and then begins to expand outward from there—the loss of hours, cities, rivers, an entire continent. It’s a poem, perhaps, best heard because the sound of the poem is so important to its meaning. A reading of the poem begins at 1:50 here: I appreciate this reading. I appreciate the shift and sigh in the reader’s voice when she reads about the loss of the mother’s watch–and how her voice sustains that shift through the remainder of the poem. If you listen to the full 6-minute video, you’ll learn that Elizabeth Bishop lost both her parents before the age of five. Knowing an author’s story doesn’t always change the experience of a poem, but for me, this piece of history does seem crucial. The tone of the poem seems important. The seriousness and the lack of seriousness. Both. It seems just the kind of poem that could inspire writing. What has been lost? One could make a list. It could begin with keys and socks. And it could go on from there. And the list could lead to the question: Does the practice of loss carry us anywhere? Does the practice of loss make it become any more bearable? Any less of a disaster? And what might the practice of loss look like? I keep thinking that this poem is titled “The Art of Losing,” but it’s actually called “One Art” which for me is a kind of reminder that she’s talking about one art among many. A full text of the poem can be found at Poetry Foundation Image is of Paul Cezanne’s “Study of An Apple” from...

read more